On Quicksilver, Sulfur, and the Elements

Rufus starts a question with a couple objections: "What is liquified by heat is not solidified or coagulated by it; ductibles are liquified by heat, therefore they are not coagulated by it.

"Again, it was previously established that things that start coagulation with heat and end with cold are insoluble. So since ductibles are liquifiable their coagulation may not begin with heat and end with cold."

This is the modern periodic table of elements, which you might have encountered while studying chemistry. An element is a building block - every substance is composed of elements.

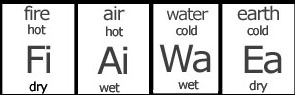

Aristotle bases all chemistry on a tiny set of elements. If medieval philosophers had had a table of elements, it would have looked a bit like this:

Fire, air, water, earth - the four basic elements according to Aristotle. Working with these four elements and other criteria, Aristotle sets out to classify nearly everything. In just one short passage from his Meteorology 4.10, he lists:

- gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, glass

- wine, urine, vinegar, lye, whey, serum

- iron, horn, nails, bones, sinews, wood, hair, leaves, bark

- amber, myrrh, frankincense, tears, stalactites, fruits, grain, salt, natron (what is natron?

)

) - blood, marrow

Then Aristotle explains how each substance is based on different combinations of the elements. For example, blood is based on three elements: earth, water, and air. The components of a substance determine how it reacts when heated, compressed etc.

Bartholomew and Rufus

Our thirteenth-century Bartholomew, Bartholomeus Anglicus (the Englishman), naturally quoted Aristotle's Meteorology, but not directly. Instead he consulted Richard Rufus of Cornwall's commentary for his discussion of minerals. Surviving in Erfurt in the same manuscript with other works by Rufus are a set of questions on Meteorology, and that is where we got our excerpts for this lesson.

But alas these questions do not include all the passages Bartholomew quoted. Maybe he used a longer version, or maybe he used a different work altogether. We're not sure whether the text you are about to read is part of the lost work Bartholomew used. Still, it very much resembles Rufus' other question commentaries, so it is quite likely that we've found Rufus' Meteora. But since nobody knows for sure right now, when you read "by Rufus" in this introduction, you should keep in mind that it is really by "Rufus (?)".

What bothers Richard Rufus?

Richard Rufus worries about whether Aristotle is consistent. Aristotle holds that opposites have opposite effects (Chapter 6). If fire can melt a substance, then that substance must contain at least some water. But if water can melt it, then the substance must be earth-based. In Question 43, Rufus draws attention to the fact that Aristotle's classification scheme gets messed up because Aristotle writes that both heat and cold can solidify certain bodies.

In Question 44, Rufus raises doubts about water from Meteora 4.9 by Aristotle. Aristotle says that water is not ductile. But in another work, De sensu et sensibilibus 4, he at least implies that it is, because water is less ductile than oil. From that it can be inferred that water is at least somewhat ductile.

In Question 45, Rufus considers a property Aristotle does not: moblity. So if mercury is dry, why does it roll around on a flat surface? Answer: its dryness is too subtle to hold its watery qualities in check.

Who turned Rufus on to metallurgy?

Avicenna's Kitâb al-Shifa, known in the West as De congelatione et conglutinatione lapidum (On the solidification and cementing of rocks) was often added to Aristotle's Meteorology. More than Aristotle, Avicenna was a rich source of provocative information for curious would be alchemists.

What makes this text exciting?

The Theory: The properties of metals can be explained by the proportions of sulfur and mercury (known to medieval authors as quicksilver) in their composition.

The Example: In explaining the properties of silver, Bartholomew says that silver has less sulfur and more water, air, and mercury in its composition, citing Richard Rufus as his authority. De argento. ... Plus autem est ibi de aereo et aqueo et argento vivo quam sulphuris, et ideo non est tanti ponderis sicut aurum, ut dicit Richardus Rufus (DRP 16.7).

The Practice: Since the proportion of sulfur in silver is low, it is not as heavy as gold. This led to the idea that increasing the proportion of sulfur to mercury in silver would make it heavier and more like gold.

The Application: That little recipe might seem useful to someone setting out to make gold from baser metals: add sulfur.